The Cross as Touchstone

Synodality from the Way of Christ

Abstract

This article reflects on the meaning of the Cross as a spiritual touchstone for the synodal journey of the Church at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Starting from the present synodal context—characterised by listening, discernment, and shared responsibility—the author raises the question of the inner criterion by which these processes may truly remain evangelical. Against the background of accelerating social change, increasing vulnerability, and a declining self-evidence of faith, it is argued that synodality cannot be reduced to procedures or structures alone, but fundamentally requires a conversion of heart.

Within this perspective, the Cross appears not as an obstacle to renewal, but as its decisive point of orientation. In dialogue with Sacred Scripture, the liturgical tradition, and the insights of Viktor Frankl, suffering is interpreted as a place of meaning and encounter, where human vulnerability can be transformed into love and fruitfulness. The history of the Church is thus understood as a paradoxical “triumphal march of the Cross”: sustained not by power or success, but by fidelity, sacrifice, and hope.

The article concludes that the future of the Church does not lie beyond the Cross, but within its depth. Only where synodal discernment takes place under the sign of Christ’s Cross can the Church grow into a credible community of hope and courage. In this way, the Church is portrayed as a pilgrim people: journeying in Christ, with Christ, and as the Church of Christ, sustained by the hope that springs from the Cross and points forward to the Resurrection.

Introduction

The Church in 2026 finds herself at a crossroads. Across the world she is engaged in a synodal process: listening attentively, discerning together, and seeking paths of fidelity and renewal. This journey is carried by a deep desire to be Church with people, among people, and for the world of today. At the same time, this path inevitably raises fundamental questions: where are we going? What is the inner compass guiding this shared journey? And by what measure do we discern whether our paths are truly evangelical?

In a time marked by rapid social change, diminishing religious self-evidence, and heightened sensitivity to suffering, vulnerability, and injustice, the Church cannot suffice with structures, procedures, or statements alone. Synodality demands more than consultation or participation; it calls for conversion of heart. Precisely at this point, a voice is heard that is not always comfortable, yet remains decisive: the voice of the Cross.

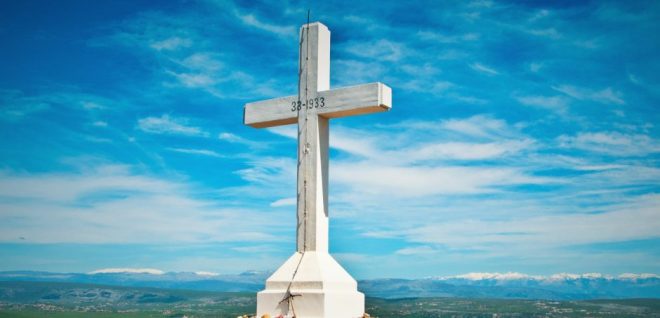

The Cross is neither a marginal element of the Christian faith nor a burden from the past that can be set aside. It is the sign in which the path of Christ himself becomes visible: a path of self-giving, of fidelity amid adversity, of love that does not withdraw from the suffering of the world. For a Church seeking to discern together, the Cross is not an obstacle but a touchstone. It guards against superficial adaptation as well as against rigid closure; against power without service and involvement without truth.

This reflection seeks to open a spiritual horizon for our time. It invites the synodal journey to be understood in continuity with what has sustained and renewed the Church throughout the centuries: not success or visible strength, but the quiet and paradoxical fruitfulness of the Cross. Only where the Church dares to walk this path—listening, suffering, and loving—can she truly become a sign of hope for the contemporary world.

What follows is a testimony to this conviction: that the future of the Church does not lie beyond the Cross, but within its depth. There, where suffering is borne and shared, new meaning emerges, new life springs forth, and genuine communion grows. The synodal Church is truly on the way only when she dares to remain together under the sign of Christ himself.

The Triumphal March of the Cross – Suffering as a Path to Meaning

Whoever looks back on what the Church has brought forth in her journey through the centuries (*), cannot fail to be struck by a sense of awe. Her enduring unity amid division, her universal reach across cultures and epochs, and her countless fruits of holiness and mercy all testify to a vitality that transcends purely human explanation. Yet a closer examination raises a surprising question: what has been the deepest and most effective source of the Church’s resilience and renewal?

The answer reveals itself in an apparent paradox. The triumphal march of the Church is, in its deepest sense, a triumphal march of the Cross. Not of the Cross as a decorative or rhetorical symbol, but of the Cross in its full seriousness: an existence marked by suffering, loss, persecution, and inner self-emptying. The Church’s prayer expresses this succinctly: “We adore you, O Christ, and we praise you, because by your holy Cross you have redeemed the world.” In this confession lies the fundamental motif of the whole of Church history.

To be Christian is to follow Christ. And to follow Christ means not merely to imitate him in words or ideals, but to walk his path of self-giving. “Whoever does not take up his cross and follow me is not worthy of me” (Mt 10:38). These words constitute an invitation to truth: whoever denies or flees suffering ultimately loses himself; whoever bears suffering in love discovers a deeper meaning that transcends the limits of earthly life.

At this decisive point, the Christian faith converges with the insights of Viktor Frankl. In the midst of the extreme dehumanisation of the concentration camps, Frankl discovered that suffering in itself does not confer meaning, yet the human person remains free to give meaning to suffering. When suffering becomes unavoidable, the decisive question is no longer why it happens, but for what it is borne. In this inner stance, Frankl recognised a final and inviolable freedom.

Christian faith goes still further. It perceives in suffering not only an existential task, but a place of encounter. The Cross becomes a guiding principle for Christian life: whenever it appears, new possibilities of life open up—paradoxically so. Not because suffering is good in itself, but because suffering borne in love can be transformed into love. Just as the grain of wheat must die in order to bear fruit (Jn 12:24), so human existence becomes truly fruitful only when it dares to let go of itself.

For this reason, it should not surprise either the Church or the individual Christian that suffering repeatedly becomes part of their path. Rather, it may be understood as a sign that God has not abandoned his Church, but allows her to walk the way of his Son. Such insight requires faith: a faith that looks beyond success or visible growth and acknowledges that “the wisdom of this world is folly in the sight of God” (1 Cor 3:19).

The sacrifice of Christ on Calvary was accomplished once and for all, yet it continues to live mystically at the heart of the world. In the Holy Eucharist it transcends the boundaries of time and space and gives value and direction to every human offering. In the light of this one sacrifice, human suffering also receives a new meaning: it becomes not destructive, but transformative.

Attempts have been made to reduce the Cross to a symbol of violence or oppression, even to a source of human misery. This is the tragic error of a worldview that recognises only what is immediately visible. In truth, the Cross—through all its pain—is the supreme revelation of love. Not hell, but heaven, because it is the ultimate gift of self. Here the deepest mysticism of Christianity touches the deepest dimension of human existence: life arises where love gives itself away.

The sufferings of the Cross are therefore not an endpoint, but birth pangs. They precede the emergence of the new human being. This new human being is Christ himself, yet he lives and works in the hidden depths of every soul. In each of us this new life has been planted as a divine seed, a germ of eternal life, unfolding slowly and often through pain.

Concluding Reflection

Pilgrims of Hope and Courage in Christ, with Christ, and His Church

At the conclusion of this reflection, we do not come to a standstill, but continue our journey. To be Church is not to complete a project, but to walk a path: a pilgrimage through history, sustained by hope and often tested in courage. In our synodal journey, we discover time and again that we do not walk this path alone. We walk in Christ, with Christ, and as the Church of Christ.

The Cross, which has accompanied this reflection as a touchstone, proves to be not a sign of stagnation or defeat, but of orientation. It guards against the illusion that renewal can occur without sacrifice, that communion can endure without truth, or that mission is possible without self-giving love. The Cross keeps the Church centred on what is essential: that her path remains inseparable from the path of her Lord.

Thus we become pilgrims of courage. Not because suffering disappears, but because it is borne together. Not because everything becomes transparent or easy to understand, but because nothing need be meaningless when entrusted to God. In Christ we recognise that suffering does not have the final word. His Cross already bears within itself the sign of the Resurrection. Christian hope, therefore, is not optimism, but trust: trust that God is at work even where we experience fracture and vulnerability.

This path demands courage: courage to continue listening when differences cause pain; courage to discern together without abandoning one another; courage not to absolutise one’s own position, while remaining faithful to the Truth entrusted to the Church. To be a synodal Church means not to carry one another despite the Cross, but under the Cross.

In the Holy Eucharist this mystery remains present among us. There the one sacrifice of Christ is made present, and we are formed anew into communion. There we learn that our own lives—with their joy and their burden—may be taken up into God’s redeeming love. Thus the Church becomes not a refuge for the strong, but a home for pilgrims; not a place of perfection, but of hopeful fidelity.

Therefore we may continue our journey—not unbroken, but undaunted. As pilgrims of hope and courage, sustained by Christ and united in his Church. With the Cross not as a burden upon our shoulders, but as a sign before our eyes. And with the ancient yet ever new confession upon our lips—simple, steadfast, and full of trust:

O Crux ave, spes unica.

Hail, O Cross, our only hope.

Footnote

(*) Cf. The Catholic Church, Doctrine and Apologetics, edited by Prof. D. Bont and Dr. C. F. Pauwels O.P., N.V. Zonnewende Kortrijk / Het Spectrum Utrecht, second volume, Books 14–25, pp. 1006–1008.

Author

Pastor Jack Geudens

Smakt, 19 January 2026