The Inner Authority of the Church under the Sign of the Cross

A Contribution from Passionist Spirituality to Contemporary Synodal Discernment

Rev. J. Geudens, Smakt 2026

I. Introduction – Authority in a Time of Synodal Reorientation

The contemporary Church frequently speaks of synodality, discernment, and shared responsibility. These terms point to a genuine need: the desire to rediscover the Church as a listening community, journeying with and toward Christ. At the same time, it is becoming increasingly clear that the crisis in which the Church finds itself is not primarily organizational or methodological, but spiritual and theological in nature. What is at stake is the authority of the Church—not so much her juridical competence or institutional legitimacy, but her inner authority: the authority that arises from participation in the truth of Christ Himself.

This inner authority is neither a vague charisma nor the result of consensus-building. It is rooted in the revelation of God in the crucified Christ. Where this foundation becomes obscured, synodality risks shifting from spiritual discernment to procedural consultation; from communio to consensus; from obedience to the truth to legitimacy conferred by majority vote. It is precisely here that the spirituality of the Congregation of the Passionists can offer a decisive contribution.

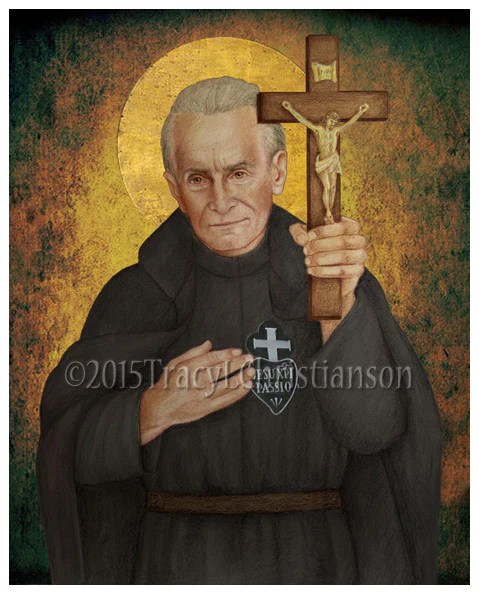

From its very origins, this Order has borne the charism of the memoria Passionis: the living remembrance of the suffering and death of Christ as the source of salvation, truth, and renewal. For Paul of the Cross, the founder of the Order, the Cross was not a devotional accent but the hermeneutical center of Christian life. In the Cross, God’s wisdom is revealed—a wisdom that does not abolish human reason but purifies and orders it. Where the Church no longer measures her decisions, her ministry, and her discernment against this wisdom, she loses her spiritual gravity, and authority comes to be experienced as coercion or mere function.

Speaking of inner authority directly touches upon the current synodal debate. The Second Vatican Council emphatically pointed to the mystery of the Church as the Body of Christ and the temple of the Holy Spirit, in which office, charism, and conscience find their place within a single economy of salvation.¹ Yet the question remains how this conciliar framework becomes concretely operative in a context in which bearing the Cross is marginalized and obedience is often reduced to functional compliance or psychological well-being. Passionist spirituality recalls that true discernment is possible only where one is willing to let truth weigh upon oneself—even when it confronts and wounds.

This contribution proceeds from the thesis that the authority of the Church is primarily inner in nature: it arises where persons—and especially those who hold office—are inwardly formed by Christ’s self-gift. This authority cannot be produced by structures, nor replaced by processes. It is received to the extent that one shares in the suffering, obedience, and wisdom of the Crucified. In this sense, the Cross does not stand alongside synodality, but functions as its normative criterion.

The Passionist tradition thus closely aligns with other spiritual and theological trajectories within the Church that often run in parallel but are rarely brought into explicit dialogue. It shows a deep affinity, for example, with the theology of the priesthood developed by Armand Ory, who understands ministry as an existential sign of God’s merciful love, rooted in sacrifice and truth.² Likewise, there is an intrinsic coherence with the devotion to the Holy Head of Jesus, as entrusted through the mystical vocation of Teresa Helena Higginson—a spirituality in which the human intellect is healed through participation in Christ’s suffering and obedience.³

By bringing these lines together, this article seeks to contribute to the current conversation on synodality and ecclesial authority—not by introducing new models or terminology, but by returning to a proven spiritual intuition: that the Church possesses authority only where she lives from the Cross. The Passionists preserve this insight as a prophetic memory within the Church. Their spirituality reminds us that truth is not constructed but received; that obedience is not humiliation but participation; and that authentic renewal never comes about apart from the suffering of Christ.

In a time when the Church is searching for direction and credibility, this Passionist wisdom can help purify synodality of its one-sided tendencies and re-anchor it in its deepest source. The inner authority of the Church is not safeguarded by more voices, but by deeper listening—to the point where Christ gave His life “to the end.”

II. Christ’s Inner Authority: Origin and Measure of Ecclesial Authority

The authority of Christ in Sacred Scripture is inseparably bound to truth and self-gift. When Jesus speaks to Pilate about His kingship, He does not appeal to power, but to witness to the truth (John 18:37). This truth does not coerce from without, but exercises authority through inner evidence. It is recognized by those who are “of the truth.”

This fundamental biblical datum constitutes the starting point for any authentic understanding of ecclesial authority. The Second Vatican Council explicitly affirms this derivative character of Church authority by stating that bishops and priests do not speak on their own authority, but in persona Christi Capitis.¹ This means that their authority is sacramentally grounded, yet existentially credible only insofar as they inwardly share in Christ’s obedience.

Passionist spirituality articulates this insight with particular radicality. For Paul of the Cross, the Cross is the place where Christ’s authority manifests itself most purely—not as power over others, but as absolute availability to the will of the Father.² Christ’s authority there is not a juridical datum, but an inner necessity arising from love.

This vision prevents two opposite distortions: on the one hand, authoritarianism, in which authority is detached from truth and sacrifice; on the other hand, relativism, in which truth is subordinated to subjective experience or consensus. Inner authority is not a middle position between the two, but belongs to a different order altogether: it is authority that is recognized, not imposed.

III. Memoria Passionis: The Cross as Hermeneutical and Criteriological Principle

The Passionist core intuition of the memoria Passionis deserves further theological elucidation. It does not merely refer to a pious recollection, but to an active making-present of Christ’s suffering within the life of the Church.³ This presence is normative: it functions as a criterion for truth, discernment, and authority.

From a patristic perspective, this closely aligns with the soteriology of Irenaeus of Lyons, for whom Christ’s obedience unto death constitutes the decisive turning point in salvation history.⁴ The Cross is not a contingent event, but the necessary form in which the truth of God reveals itself to humanity after the Fall.

A crucial ecclesiological consequence follows from this: where the Church no longer measures her speech and action by the Cross, she loses her hermeneutical key. Synodal processes then risk being evaluated according to effectiveness, inclusivity, or consensus, rather than truth and holiness.

The Passionists remind the Church that discernment is never neutral. It requires an inner positioning beneath the Cross. Without this positioning, synodality inevitably becomes procedural.

IV. Excursus I – Truth, Suffering, and Discernment in the Patristic Tradition

The early Church never separated truth from suffering. For the martyrs, the truth of faith was not an abstract doctrine, but an existential commitment. Ignatius of Antioch describes his martyrdom as the place where he truly becomes a disciple of Christ.⁵

Athanasius of Alexandria likewise connects the truth of the Incarnation with the suffering of the Church: whoever confesses the true Christ necessarily shares in His rejection.⁶ This patristic line underscores that truth proves itself not by success, but by fidelity.

Passionist spirituality explicitly stands within this tradition. It safeguards the Church from reducing truth to communicatively manageable formulations. Truth demands the bearing of the Cross—even in ecclesial decision-making.

V. Inner Authority and Conscience: Between Subjectivism and Obedience

One of the most delicate questions in contemporary ecclesial discourse concerns the relationship between Church authority and personal conscience. Conscience is frequently presented as an autonomous instance set over against the magisterium. This approach, however, stands in tension with the classical Catholic understanding of conscience.

According to Thomas Aquinas, conscience is not a source of truth, but a judgment that applies truth.⁷ Its normativity derives from the objective order of the good. Where this order is abandoned, conscience loses its orientation.

Passionist spirituality concretizes this by situating conscience under the contemplation of the Crucified. Conscience is formed through participation, not confirmed in autonomy. This closely resonates with the affirmation theory of Anna Terruwe, in which psychological maturation is never detached from moral and spiritual ordering.

Bernard of Clairvaux likewise emphasizes that true freedom is possible only in obedience to God.⁸ Obedience is not heteronomy, but participation in a higher order of truth.

VI. Ministry as Sacramental Bearer of Inner Authority

Ecclesial ministry participates in a unique way in the inner authority of Christ. This participation is sacramentally grounded, yet existentially mediated. When ministry is detached from sacrifice and self-gift, it loses its transparency.

Here the thought of Armand Ory closely aligns with the Passionist intuition. Ory describes the priesthood as a sign of God’s merciful love, while emphasizing that this mercy is never separated from truth and sacrifice.⁹ The priest represents Christ not through functionality, but through conformity.

From a canonical perspective, this is confirmed by the very purpose of Church law: salus animarum suprema lex (can. 1752 CIC). This principle presupposes inner authority. Without inner participation in Christ’s self-gift, the salvation of souls is reduced to organizational care.

VII. Excursus II – Canonical Authority and Spiritual Authority

Canon law implicitly presupposes a spiritual understanding of authority. Although the law is formal and juridical, it can function only within an ecclesiology of communio. When canonical authority is detached from spiritual authority, legalism emerges.

Passionist spirituality serves here as a corrective. It reminds us that authority is not legitimized by law alone, but by truth and holiness. In this sense, canon law is not an alternative to inner authority, but an instrument that lives from it.

VIII. The Holy Head of Jesus: Healing of the Intellect under the Cross

The devotion to the Holy Head of Jesus, entrusted to Teresa Helena Higginson, offers a surprisingly complementary deepening.¹⁰ This spirituality emphasizes that the human intellect is not abolished by revelation, but healed.

In a culture in which rationality is either absolutized or distrusted, this devotion offers a theological balance. Thought is brought beneath the Cross—not to be destroyed, but to be purified of pride and autonomy.

This intuition is deeply Passionist: here too, suffering is the place of wisdom. Christ teaches not only what we are to think, but how we are to think—namely, in obedience.

IX. Synodality as Paschal Discernment

Synodality can bear fruit only when it is understood as a paschal path. Discernment is not neutral dialogue, but a shared journey beneath the Cross.

The Emmaus narrative (Luke 24) serves here as a fundamental paradigm. Only when Christ interprets the suffering do the Scriptures become intelligible and the eyes are opened. Without this paschal interpretation, conversation remains closed.

Passionist spirituality protects synodality from devolving into process-thinking. It reminds us that true discernment always demands a truth that can wound.

X. Concluding Reflection – The Passionists as the Prophetic Memory of the Church

In a Church seeking direction and credibility, the Passionists preserve an essential memory: that truth suffers, authority sacrifices, and obedience gives life. The inner authority of the Church is not reformed by structures, but rediscovered by returning to the Cross.

Synodality finds its truth not in methodology, but in participation. Only where the Church is willing to lose herself with Christ will she rediscover her authority.

Footnotes

- Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, nos. 18–27.

- Paul of the Cross, Lettere, critical edition, Rome.

- Congregation of the Passionists, Constitutiones, arts. 1–6.

- Irenaeus of Lyons, Adversus Haereses, V, 16–21.

- Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, 4–7.

- Athanasius, De Incarnatione Verbi, 20–25.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I–II, q. 19.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, De diligendo Deo, I–III.

- Armand Ory, Le prêtre, signe de la Miséricorde, Paris 1954.

- Teresa Helena Higginson, Letters and Spiritual Writings; Z.E.P. Marcel OFM Cap., Handbook for the Devotion to the Holy Head of Jesus.

Author Profile

Jack Geudens is a Roman Catholic priest and emerging writer working at the intersection of spirituality, pastoral theology, and Christian anthropology. His thought and writing are characterized by an explicitly Christian-holistic vision of the human person, in which body and soul, the beginning and completion of life, vulnerability and dignity are understood as a single coherent theological whole.

A constitutive element of his work is his deliberate positioning as a pro-life priest. This choice is not understood as a merely ethical or political stance, but as a consequence of a Christologically grounded anthropology. Human dignity is not derived from autonomy, functionality, or social recognition, but from God’s creative and redemptive action. In his work, pro-life therefore does not appear as a separate moral theme, but as an integral attitude flowing from the confession of Christ, crucified and risen.

The spiritual center of his theological reflection lies beneath the Cross, which functions as a normative locus for truth and discernment. Within this paschal hermeneutic, the Cross is not reduced to a symbol of suffering, but understood as the place where the truth of God and the truth of the human person are definitively revealed. From this perspective, Geudens adopts a critical stance toward pastoral and ecclesial renewal approaches that fragment life or address it selectively.

His spirituality is essentially Marian. Mary functions in his work as an ecclesiological and spiritual model: she receives life, preserves it, and carries it—even when that life is marked by suffering. Within this Marian perspective, the Resurrection receives its full theological meaning, not as a denial of guilt or loss, but as God’s eschatological fulfillment of what remains broken. This approach gives pro-life thought a deeper spiritual and ecclesiological grounding.

The pastoral concretization of this vision is expressed, among other things, in his involvement in post-abortion ministry, particularly within the context of Rachel’s Vineyard. Here his holistic anthropology becomes visible in an integral approach to the person, in which moral responsibility, psychological vulnerability, and spiritual healing are held together. Guilt is not relativized, but taken up into a process of reconciliation; pain is not reduced to psychological pathology, but spiritually lived through.

Methodologically, his pastoral theology is also shaped by his background in occupational therapy and psychosocial care. This experience has preserved his thinking from abstraction and one-sided spiritualization. Geudens emphasizes that healing and integration often begin in meaningful action: rhythm, responsibility, symbolic and liturgical practices that support the inner process. The human person is approached not as a case, but as a person in becoming, called to renewed coherence.

For Geudens, the priesthood is understood as sacramental presence at the mystery of life—received, wounded, forgiven, and restored. His writing is an extension of this pastoral praxis. He does not aim at persuasion through slogans, but at opening space for truth that heals. In his work, mercy and truth are not dialectically opposed, but mutually presupposed: true mercy presupposes truth, and true truth safeguards life.

Within the broader ecclesial debate, Geudens positions himself critically with respect to both moralistic reductions of pro-life and pastoral approaches that suspend normativity. His contribution seeks an integration of anthropology, spirituality, and pastoral practice, in which reverence for life in all its phases is understood as a constitutive element of Christian faith and ecclesial praxis.